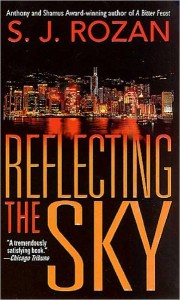

Reflecting the Sky interview

Q: Your Lydia Chin/Bill Smith series is distinguished by two main features. Besides the exceptionally lyric prose, I mean. The two features, of course, are your Chinese protagonist, Lydia Chin, and the way you alternate Chin’s and Smith’s voices from book to book. Let’s start with Lydia. Where did she come from?

A: Bill Smith was the first character I had. His was that alienated voice-over that I’d been hearing in my head for a lot of years. When I finally came to write about him, I wanted him to have a sidekick, but someone different from him. For me, the P.I. form is all about moral ambiguity, and to have the PI constantly forced to question his own assumptions on every level is a critical part of the kind of outsider position I wanted to write about. So Smith’s sidekick needed to be a woman because he’s a man, small because he’s big, young because he’s middle-aged, athletic because he’s an intellectual—and then I thought, hell, why not go for the whole nine yards (a construction expression, by the way) and make her someone from a different ethnic group so that everything he thinks he knows is up for grabs.

Q: And why Chinese? Are you part Chinese?

A: Not any part. But I’d always been interested in China, I’ve always had Chinese friends—the Chinese have never seemed “exotic” to me, their culture hasn’t ever seemed “impenetrable” or, god help us, “inscrutable.” It’s always seemed like an interesting culture and history, one that can be studied and learned about just like mine (Eastern European Jewish) or anyone else’s. So I studied, and I hope I’ve learned.

Q: Okay, now the alternating narrator thing. Why not choose one and underline?

A: Well, Lydia was created as a sidekick for Bill, but that lasted about three chapters into the first book I started. Then two things became clear. One, that she could hold her own and in fact was extremely competitive with anyone she cared about, like Bill; probably that comes from having four older brothers. And two, that the whole thing—that is, the story I was telling in that book—probably looked very different from her side. So I wrote a short story from her point of view, to see if she really emerged as a full-bodied character, and I thought she did. I finished that Bill Smith novel, and then I gave her a book of her own. That became China Trade, the book St. Martin’s published first.

Q: But that didn’t mean you were finished with Bill Smith?

A: Not for a minute—I never intended it to. But because Bill and Lydia are so different, they can handle different material. Although every book I write is in some way about the necessity but near-impossibility of connections, Bill and Lydia approach this topic from opposite sides: she from inside a large, extended Chinese family, with her whole life ahead of her, he from a position of isolation and loss. So I can tell different stories, depending on whose book it is.

Q: Reflecting the Sky is set in Hong Kong. Why?

A: One reason is that the last Bill Smith book, Stone Quarry, was set in another county, so Lydia, competitive as she is, wanted a book set on another planet. I couldn’t manage that, but Hong Kong fascinates me. I’d been there twice, and from the first minute I set foot in the place I knew I’d have to set a Lydia book there. When it was time to do Reflecting the Sky I went back another time and did research.

Q: What is it about Hong Kong?

A: The dual identity. Part British, part Chinese, completely neither. The entire place shares Lydia’s inablility to quite fit anywhere. It’s as much an outsider to both its cultures as Lydia is to hers. So that became the theme of the book: duality.

Q: What kind of an experience has writing been?

A: Fun and agonizing. Research is unmitigated fun, even when it’s raining, even when you don’t speak the language or you’re upstate and the car breaks down. Everything is research, which means that situations that might have been boring or annoying if you weren’t writing become fascinating (even if they’re still annoying). Research in its best form legitimizes studying anything you want to study. In its worst it legitimizes snooping and spying and eavesdropping. All of that is fun.

Writing is agonizing, though not unmitigatedly. When it works well, when you get the “flow”, it’s exhilarating. And writing’s great saving grace, to me, is that when it isn’t working at least I know it.

Q: What’s the most unusal thing about you as a writer?

A: The only unusual thing may be this: as an architect, I’m used to creativity being an “iterative” process. That is, you do something, you see what you’ve got, you add something, you change what you did in the beginning based on what you just did, you see what you’ve got again, you add some more, you see again, you change, you add… So it doesn’t throw me to change, to rewrite, to toss away something good if it doesn’t add to the book or is in the wrong place. I’m also used to everything having to have more than one purpose, to a good solution being one that solves more than one problem. I don’t know how unusual any of this is, but I know my writing process comes out of the process of architectural design.

Q: You’ve won the Shamus and Anthony Awards for Best Novel, and been nominated for the Edgar. What worlds are there left to conquer?

A: Actually, the award I’m proudest of is the Nevermore from Partners in Crime, one of the independent mystery bookstores in New York City. The Nevermore, given the night before the Edgar banquet in the spring, is sort of the anti-Edgar. I won the “Hauled Ashes Award” for the fictional couple most in need of getting it on.

Q: Which brings us to the question: will they or won’t they?

A: Do I know? I’m only the writer.