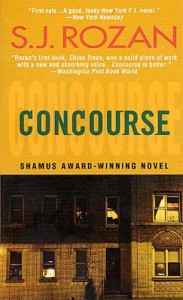

Concourse

Chapter One

At Mike Downey’s wake the coffin was closed.

In the large front room at Boyle’s Funeral Home darkdressed women kissed each other’s cheeks, murmured gentle words. The older men stood together in small groups, looked uncomfortable in out-of-date suits; the younger ones, Mike’s friends, passed a surreptitious flask, and told each other stories about Mike they’d all heard a hundred times, and laughed too loudly at the stories.

Bobby Moran nodded to me across the flower-choked room. He spoke parting words to the men around him and headed over. His limp was worse than I’d seen it, giving him a halting, rolling gait.

“Kid,” he said. “Thanks for coming.” His face, usually ruddy, was gray, the slackness on the left side pronounced. His blue eyes were pale, washed-out. Twenty-five years ago, when I’d met him, Bobby Moran’s eyes had been sharp and clear as a January morning.

“I’d have come anyway,” I told him. “Even if you hadn’t called.”

“I was afraid you’d be out of town. Upstate.”

Bobby knew me well enough to know that about me: that I try, if I can, to spend some time at my cabin this time of year. I was born in the South, raised on Army bases in Europe and Asia, and though I’ve lived in New York since I was fifteen, the extravagance of an eastern hillside in autumn still amazes me.

“I was going,” I told Bobby. “I put it off.”

“Thanks.” He looked away. “Seen Sheila yet?”

“Just now.” Mike’s widow, to whom I’d said clumsy words, sat by the coffin. She was quiet, but she seemed to be trembling inside, like a teardrop.

Bobby and I stood in silence for a moment, surrounded by voices and soft light. The air was sweet with white roses, camellias, lilies. Bobby said, “I need you, kid.”

“I owe you, Bobby. You know that.”

He scowled. “No, to hell with that. I’ll hire you. I’ll pay you. Pay you better than the dumb fucks who work for me now. Pay you better than I used to.”

I shook my head no. He nodded his yes.

“It’s just–I’d do it myself,” he said, his voice tight with targetless anger, “but I can’t. I’ve got no one else to ask, kid. I’ve got no investigators anymore. I gave that up, because of thisÖ” He trailed off, gestured at his left side, where the arm hung slack and the leg limped. “This” was Bobby’s stroke. “But the guard business, I thought I could keep that up. Take dumb fucks, train ’em and pay ’em, how hard could that be? How goddamn hard?” He didn’t meet my eyes.

“Come with me,” I said.

We worked our way through the crowded room, Bobby’s eyes fixed savagely ahead, acknowledging no one’s words of comfort or greeting.

We crossed a deeply carpeted hall to a small, plain chapel where a crucifix hung. Beside it a stained-glass St. Patrick, staff raised and halo glowing, drove the snakes out of Ireland. The panel shone from behind, lit by fluorescent lights. Bobby gave me a shaky grin.

“Ah, piety,” he said.

From my jacket pocket I took my own surreptitious flask, handed it to him.

“I’m not supposed to,” he told me.

“Who is?”

He eased onto an upholstered folding chair. The chairs were set in rows; I swung one around to face him. He pulled on the flask, handed it back.

“It wasn’t your fault,” I told him, words no one who needs them ever believes.

“Yeah,” he said. “My sister’s son. The dumb fuck.” He looked at St. Patrick, or maybe at the snakes. He said to me, “How soon can you start?”

I drank from the flask. I’d filled it with Bushmill’s, Bobby’s drink, thinner than my bourbon, and smoother. “Just tell me what you want me to do.”

Bobby turned away from St. Patrick, to me. “Do? Do what I goddamn taught you to do, kid. Do your job.” He looked around the chapel as though searching for something to help him say the words. “Find out who killed Mike.”