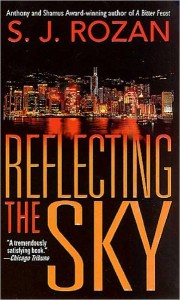

Reflecting the Sky

Excerpt

Damp, soupy heat washed over me as I pushed out through the revolving door. The bright morning glare was already hazed up by the shimmering exhaust of a river of cars, buses, and trucks. I looked left, looked right, got my bearings, and headed briskly down the sidewalk.

“Come on!” I turned to yell to my partner, Bill Smith, who still stood, looking a little groggy, his hands in his pockets, just gazing around. “Relive your misspent youth some other time! I don’t want to be late.”

With muttered words I was just as happy not to hear, he lurched down the sidewalk after me. Jostling, rushing pedestrians, many of them yelling into their cell phones, hurried past in both directions, making me feel like I had to work to keep my footing or I’d be tossed on their tide and swept away. Bill caught up to me as I stopped at the first corner, waiting with a crowd eight deep for the light to change.

“Late is extremely unlikely,” he grumbled, taking advantage of the momentary halt in our forward charge to light a cigarette. “Impolitely early, maybe. We’re twenty-five minutes ahead of even your obsessive-compulsive schedule. Will you slow down? And how do you know where you’re going? I thought I was supposed to be your native guide.”

“I don’t know what you’re supposed to be doing,” I said as the light turned green and the crowd surged forward, “but it can’t be guiding me around a place you haven’t been in for twenty years.”

A horn blasted as the last stragglers from our pedestrian stream leaped up onto the curb to avoid being mashed by a bus. The hiss and rumble of tires, the squeal of bus brakes, and the endless rattle of jackhammers from nearby construction made conversation difficult, but I was too keyed up to talk, anyway. The wind shifted, stirring the smells of diesel fuel and salt water into the scents of softened asphalt and frying pork already thick in the air. They were exciting smells, and it was an exciting morning, all the rushing, rumbling, surging, and yelling in the brightness. Though I didn’t see, really, why I should be so affected by it. I’ve spent my entire life negotiating traffic, noise, glare, and sidewalks. I’m Lydia Chin, born and raised in Chinatown, a genuine native New Yorker.

Of course, this wasn’t New York. This was Hong Kong, City of Life.

Life, pork, exhaust, and pedestrians. Bill matched his pace to mine and we hurried down the sidewalk in the sticky heat. Being from Chinatown, I was better at this business of threading through dense, moving crowds of Chinese people than he was, though the streams on the sidewalks of home had never flowed this fast. We kept being separated, coming together, getting pushed apart again. But we both knew where we were going–he because he had been here before, on R and R leaves in the navy; me because I had been studying maps for a week–and we ended up together and exactly where we wanted to be, at the turnstiles of the Star Ferry.

At which point I glanced at my watch, and then, because I know my watch, at his. “Wait,” I said. “As you so accurately, although crabbily, pointed out, we’re still early. The ferries run every eight minutes. Let’s take the next one. I want to see.”

He raised his eyebrows and sighed theatrically, but I didn’t care. Leaving him to follow, I zipped past the English-language bookstore, the Japanese snack shop, the newspaper vendors and the public bathrooms. The ferry terminal buildings gave way to an open promenade with a railing, and suddenly there was the Hong Kong skyline shining across the harbor.

It was as though someone had unrolled New York, slapped it with dozens of huge, neon brand-name signs visible even in the hazy sunshine, and spread it against a backdrop of mountains along a waterfront so long I had to turn my head way to the left and then way to the right to see the ends of it. Water sparkled in the sun, lapping against the seawall we were standing on. The frothy wakes churned up by barges, fishing boats, great white yachts, and tiny green sampans heading both ways through the harbor crisscrossed the trails of ferries plowing back and forth across it, from Hong Kong Island, where we were going, to the tip of the Kowloon Peninsula, where we were. The ferry we’d almost taken tooted its horn as it nosed out of its berth, and from way off to the right came a much deeper sound, some other horn saying something in the niversal language of ships.

“Close your mouth,” Bill said. “People will know you’re a tourist.”

“I’m not a tourist. We’re here on business. And why didn’t you tell me it was this huge?”

He gazed across the harbor. “When I was here, it ended about there.” He pointed with both hands at the limits of a much shorter waterfront. “And none of the biggest skyscrapers were there, and neither was that.” That was a low, swoopy building, all metallic curves and wings, shining in the sun, right in the center, right on the water. “But the impression was the same. I stood there with my mouth open, too.”

“My mouth is not open. I’m Lydia Chin. Stuff like this doesn’t impress me,” I said, unable to take my eyes from the view across the water.

“I know,” Bill said. “That’s one of your best characteristics, how hard you are to impress.” He looked at his watch. “Now we’re right on schedule. We’d better go, or we actually will be late, and you’ll blame me.” “Well, it’ll be your fault,” I said, tearing myself away from the skyline, turning to hurry back to the ferry. “You’re the one with the good watch.”

“Maybe that’s why I’m here,” Bill said as we dropped our ridged coins in the ferry turnstile and headed with the rest of the crowd up the stairs. “Because I have a watch that works.”

“That’s an expensive timekeeper.” I trotted down the wooden ramp onto the boat and took a seat at the very front so I could see us sail across the harbor. “A business-class ticket and a week in a fancy hotel? It would have been cheaper for Grandfather Gao to buy me a Rolex.”

“Or he could have put me in the same hotel room as you. That would have saved him a bundle. In fact, maybe we have a fiduciary duty to our client–”

I gave his fiduciary duty a dirty look and turned back to the opposite shore; we had started to move.

As the harbor breeze blew my hair around, I watched the edges of the skyline sharpen out of the haze. The buildings grew larger and Bill sat silent beside me, watching them too. It really wasn’t clear to either of us why he was here. It wasn’t, actually, clear to me why either of us was here.

What had seemed clear a week ago when I’d first heard this idea was that I was probably hallucinating and had lost my mind. Either that, or Grandfather Gao had lost his; but even suggesting that idea to myself made me so queasy from guilt that I had to calm myself with another sip of his tea.

I still couldn’t believe it, though. “You want me to go to Hong Kong?” We were sitting at the low, lion-footed table in Grandfather Gao’s Chinatown herb shop, surrounded by the dark wood cabinets with their small drawers, the brass urns and ceramic jars, the mingled smells of sweet incense and dried herbs that were as familiar to me as the flowered upholstery, family pictures, and spicy aroma of my mother’s cooking in the Chinatown apartment where I grew up.

“With your partner,” Grandfather Gao replied. His voice was its usual calm, somber self, but even in the shop’s peaceful shadows I could see him smile at the excited squeak in my voice. He used to smile that same smile when I was seven, when I made that same excited squeak.

I tried to control myself and act dignified. I liked to think I’d changed in the years since I used to come bouncing into the shop, interrupting Grandfather Gao in the middle of weighing out herbs for a customer or reading his Chinese newspaper, to tell him about some event or idea of enormous importance to a grade-school child. After all, I’m twenty-eight, a PI with her own practice, a licensed professional. Even if my license is in a profession my entire family abhors.

So I sipped my tea calmly and regarded my prospective client professionally. He wore a dark suit and tie, with a gloriously starched white shirt, as always. His thin black hair was combed straight back from his high forehead. He reached an age-spotted hand to the teapot and poured for me, and it suddenly occurred to me that maybe I’d changed in all these years, but Grandfather Gao hadn’t, not one bit.

“I hope this is a convenient time for this journey, Ling Wan-Ju,” he went on, as though this were a normal conversation. Because we spoke in Cantonese, as we always did, he used my Chinese name, as he always had. “Your partner also, I hope he is free?”

By my partner, he meant Bill Smith. Although, unlike my family, Grandfather Gao does not regard Bill as the human equivalent of the primrose path to hell, it was still a shock to hear him suggest that Bill accompany me to the other side of the world.

Nevertheless, resolving to regain my cool professional demeanor, as befits a private investigator about to be sent overseas, I said, “Grandfather, of course I’ll do anything you ask. But you know I’ve never traveled. I may not be the right choice to perform this task for you, whatever it is.” It was killing me to say this, since I was already seeing myself in a window seat on the New York-Hong Kong flight, but it was always best to come clean with Grandfather Gao.

“Your partner has traveled,” he answered, unperturbed. “I have considered this carefully, Ling Wan-Ju. A stream undisturbed flows easily to the sea, but a stream can be diverted, set on another course. You are a person in whose ability to find the correct course I have a great deal of confidence.”

I blushed from my toes to the roots of my hair. Grandfather Gao did nothing but sit in his chair and sip tea. I sipped tea, too, and tried to act as though people who meant to me what Grandfather Gao did said things to me like he’d just said everyday of the week. When I found my voice, I said, “Thank you, Grandfather. What is the task?”

He didn’t speak right away, but looked into the shadows of his shop. Behind him, tendrils of smoke wandered into the air from the three sticks of incense burning at General Gung’s shrine, high on the wall.

“When I was a boy in China,” he said, bringing his eyes back to me, “two other boys in the village were as close to me as brothers. We were constant companions, inseparable. One of those boys was your grandfather.”

I knew that. That was why, when my parents came to America, Grandfather Gao had looked out for them, finding them the apartment my mother and I still lived in, getting my mother her first sewing job, arranging for English lessons for my oldest brother, Ted, who, along with my next-oldest brother, Elliot, had been born in Hong Kong. That was why, along with lots of other Chinatown kids whose families had been split apart when some came to America and some stayed behind, though he wasn’t really ours, we had always called him “Grandfather.”

As though he were reading my mind–a sense I had with disconcerting frequency–Grandfather Gao said, “When we were fourteen, I left China in the company of Wei Yao-Shi, the third companion of our boyhood days. Your grandfather remained in the village. We never saw him again.”

“My father always said grandfather couldn’t bear the thought of living anywhere but where his family had always lived.”

Grandfather Gao nodded. He paused, looking not at me and not, I thought, at the dark wood or the parchment scroll his eyes seemed to rest on. “I came immediately to America,” he said. “Wei Yao-Shi remained in Hong Kong for some years He brought his younger brother, Ang-Ran, out of China. The two established an import-export firm.” Now he looked at me. “When your parents left China, it was Wei Yao-Shi who sponsored them in Hong Kong.”

He stopped speaking; I waited, wondering about the slight note of worry I thought I heard behind his calm, decisive voice.

“When the Wei brothers’ firm began to do business in America,” he began again, “Wei Yao-Shi came here He opened an office. He married. He did not live in Chinatown, but bought a house in Westchester. Though he continued to spend a good part of each year in Hong Kong, he became…quite American. When you were small, Ling Wan-Ju, you met my old friend Wei Yao-Shi. He, like I, followed the progress of your family, for the sake of our friend, your grandfather.”

This was news to me. Seeing my expression, Grandfather Gao smiled. “His reports to your grandfather were quite satisfactory.”

Well, good, I thought, not sure I was quite comfortable with being watched and reported on, even if the reports were satisfactory.

“Your grandfather died many years ago in China,” Grandfather Gao said. “Now Wei Yao-Shi has died here in New York.”

At General Gung’s shrine the incense smoke seemed to shudder, as though a breeze had found a way into the shop’s cool recesses. “I’m sorry, Grandfather.”

“Thank you, Ling Wan-Ju. He was, of course, as I am, an old man.”

I didn’t at all like what that implied. “Grandfather–”

He silenced me with a look. “The seasons will change, Ling Wan- Ju. The leaves will fall.”

I knew better than to get involved when the nature metaphors began. I sat in silence, waiting for him to go on.

“Wei Yao-Shi left me with a task to accomplish. A letter to be given to his brother in Hong Kong. A keepsake to be delivered to his young grandson, also there His own ashes, to be taken home for burial. I would like you, with your partner, to do these things for me.”

We sat for sometime in the quiet of the shop, drinking tea, as Grandfather Gao explained to me the specifics of the situation. The more I heard, the more I understood his thought that things were not simple. What was involved, though, still didn’t seem like things you’d need a PI to accomplish, much less two, but I had voiced my opinion and Grandfather Gao seemed set on this path. I saw no reason to argue further.

When we were done I went home, took a deep breath, and explained my client’s request to my mother.

“To Hong Kong?” She sat on our living room couch, me beside her. The sun poured in the window, sparkling off my father’s collection of mud figures in their glass cabinet. The expression on my mother’s face was the same as it would have been if I’d told her Grandfather Gao wanted me to fly up to heaven and bring him back one of the peaches of immortality. “Gao Mian-Liang wants you to go to Hong Kong? He has chosen you for this important task?”

“With Bill,” I said. “He said Bill needs to come along.”

~I was as astounded as she was: she at what I had said, I because I had never before seen my mother at a loss for words.

I could understand her dilemma, though. On the one hand, she couldn’t imagine I could go all the way to Hong Kong, a place on the other side of the world I knew nothing about–and where almost everyone is Chinese, a state of being that according to my mother I, an American born and raised, also knew nothing about–and not screw this up. On the other hand,there was no way she could contradict Grandfather Gao’s decision in this or any other matter. And on the third hand, Bill was supposed to be going, too.

This last became her point of departure. “If you went alone,” she said, “alone, with no distraction, possibly you could accomplish this task. Or–” her whole face brightened with inspiration and relief; she had found an answer, “–or, Ling Wan-Ju, if I were to go with you, I could guide you. I could help you. I could make sure you did not fail in this undertaking, so important to Grandfather Gao”

Oh boy, I thought. But I didn’t stop her as she grabbed the red kitchen phone (“Red, most likely to bring good news”) and dialed the number at Grandfather Gao’s shop.

After that conversation, I called Bill.

“I’m coming over.”

“Good,” he said. “Why?”

“Just wait till you hear.”

It took me, adrenaline-filled as I was, about six minutes to get from the apartment to his place above the bar on Laight Street. Generally, it’s a ten-minute walk, but that’s if you walk.

Bill was waiting for me at the top of the stairs, a fresh cup of coffee in his hand. He poured hot water into a teapot as I paced the living room, outlining the job we’d been offered.

“Grandfather Gao?” Bill said. “Can I call him that? And will you please sit down?”

“Yes. And no. I can’t.”

Neatly sidestepping me, he moved to the couch safely out of my path and put his coffee on the table beside him. “Your tea’s ready. You ~want it to go?” I glared. He grinned. “Boy, I’ve never seen you like this.”

“Grandfather Gao!” I said, striding by. “Grandfather Gao wants to hire me! Do you know who he is in Chinatown? Do you know what he’s been in my life? Do you know what he is in the eyes of my mother?”

Bill did know, and I knew he did, but he asked, “What?”

“Respectability itself! The Man Who! Even my mother can’t object to my working for Grandfather Gao I mean, she does on principle because she hates this profession. But she’s secretly thrilled that Grandfather Gao thinks a worthless girl like me can be some use to him.”

“If it’s a secret how do you know?”

“She’s my mother. And Grandfather Gao” I turned and strode the other way, “Grandfather Gao could get anybody he wanted to work for him! But he thinks I’m the one who can help him out. Me! Little Ling Wan-Ju. That tomboy. That misguided problem child. And–!”

Bill waited, patience itself. Finally, after I’d done another lap, he said, “And what?”

“And he wants to send us to Hong Kong! The other side of the planet! Ted and Elliot were born there My parents used to live there”

“And Suzie Wong.”

“Hong Kong! It’s almost China.”

“It is China, now.”

“You know what I mean! I’ve hardly ever been anywhere in my whole life, and now I have a client offering me business-class tickets and a week in a hotel in Hong Kong. How can you just sit there like that?”

He picked up his coffee. “Okay, tell me again.”

“Thursday,” I said, telling him the important part. “Can you do it? Can you come?”

“He really wants me to? Why?”

I stopped pacing and just stood for a moment, looking at him. “I don’t know,” I confessed. “What he wants us to do seems pretty simple, not something a paying client might think he needs two people for. But it was his idea. He said, `Neither the little bird nor the water buffalo, different though they are, can do its work alone.”‘

“And I suppose you would be the little bird?”

I didn’t answer, because it seemed obvious. Bill sipped his coffee. “You know, of course, that the bird sits up there on the water buffalo’s rump and eats his fleas?”

I detoured into the kitchen and picked up the tea he’d fixed for me. “If you have fleas, you’re sitting in coach.”

The tea was jasmine, one of my favorite kinds, and I had to admit that over the four or so years we’d known each other Bill had learned to make a not bad cup of tea. But all I could think as I sipped it was, I wonder if they drink jasmine tea in Hong Kong.

“And what are we supposed to do in Hong Kong?” Bill asked.

“Bring a bequest to a seven-year-old boy.”

“Any particular seven-year-old boy, or do we get to choose?”

“Harry,” I said impatiently, starting to pace again. “The grandson of Wei Yao-Shi. Didn’t I tell you that already?”

“You haven’t actually said anything coherent since you got there. I think it would help if you sat down.”

“It wouldn’t I told you, I can’t.” He was following me with his head as though I were a one-woman tennis match. “Now listen: This little boy–his Chinese name is Wei Hao-Han, by the way–his grandfather, Wei Yao-Shi, just died. Mr. Wei and my grandfather and Grandfather Gao were inseparable buddies in the home village in China.”

“Used to hang out on street corners together, whistle at girls, stuff like that?”

“Certainly not. The home village didn’t have streets, just dirt paths. Can you hang out on a dirt path corner?”

“Depends on whether that’s where the girls go by.”

“Oh, of course. Anyway, my grandfather stayed there, but Mr. Wei and Grandfather Gao left to come to America when they were fourteen.”

“Looking for street corners.”

“No doubt.”

I told Bill about Mr. Wei’s younger brother, the import-export firm, the office Mr. Wei came to New York to establish, his marriage, his traveling back and forth, and the house in the suburbs.

“Now,” I said, “a month ago Mr. Wei died and left this thing with Grandfather Gao with instructions to give it to his grandson Harry and a letter to his brother at the same time and Grandfather Gao wants you and me to go to Hong Kong to deliver them. How hard is that?”

“To understand, or to do? Or to say in one breath the way you did? Because I don’t think I could do that.”

“You could if you didn’t smoke.”

“You pace. I smoke.” He struck a match and lit a cigarette, maybe to illustrate the point. I picked up pacing speed, to keep up my side.

“I understand it,” he said, dropping the match in an ashtray. “Mostly. But I do have one question. No, two.”

“Shoot.”

“You say Mr. Wei came here and married. How come he has a seven-year-old grandson in Hong Kong? Did his kids move back there?”

“Ah. I was afraid you’d ask that.”

Bill raised his eyebrows and I prepared to tell him the rest of the situation, the part that made the thing not simple. “Mr. Wei’s American son, Franklin, lives here in New York. But apparently about a year after Mr. Wei got married here he got married in Hong Kong.”

“Hmmm. Short-lived marriage, the one here.”

“Actually, no.”

“Say what?”

I took a defensive sip of tea. “Now don’t go getting all superior and moral. It’s the traditional Chinese way. A man is entitled to as many wives as he can support.”

“He is? You mean still? Today? They still do that?”

“Well, no,” I conceded. “By my parents’ time they’d pretty much stopped, and of course Mao stamped that sort of thing right out. But men of Mr. Wei’s generation–well, it happened.”

“It happened.” He was grinning. No one could ever say Bill was a handsome man, but when he grins this particular grin I sometimes have trouble staying as dignified as I like to be. “You mean, like an accident? Stumble into the church, wedding going on, you find out it’s yours? Had one already, but what the hell?”

“We don’t get married in church.”

“You’re grasping at straws. And you approve of that kind of behavior?”

“I can see certain merits,” I said airily. “The more wives there are, the less time each one has to spend with the husband.”

“A good point. I’ll remember that after you marry me. Did Mr. Wei’s wives approve?”

“At least you’ll have something to remember. They didn’t know.”

~Bill pulled on his cigarette. “Now that’s not a sign of a man with a clear conscience. When did they find out?”

“The wives? Both dead, long since, and it seems they never did know. The people who were surprised were the sons, on both sides of the planet, when the will was read. Grandfather Gao knew all along, and the younger brother in Hong Kong, but no one else did.”

“How many sons? And did Grandfather Gao approve?”

“Two: one here, one there. And when did you get to be such a puritan?”

“Hey, you’re the one who doesn’t drink, smoke, or swear. Who’d have thought that when it came right down to it you were as twisted as the next guy? Wei was supporting both families the whole time?”

“Better,” I said, leaving the next guy out of it. “He was living with both. According to Grandfather Gao, each family thought it was just an unfortunate necessity of business that he had to keep going back and forth to the other side of the world.”

“This is great. But what if they needed to talk to him when he was on the other side of the world?Wouldn’t the jig be up as soon as someone made a phone call?”

“He told both families he was staying in hotels and to contact him at work if they needed to. In Hong Kong that was the firm’s office. That’s why the brother had to know. In New York he used Grandfather Gao’s number at the shop.”

“And that worked all these years?”

“Seems to have.”

Bill finished his coffee and set his mug down. “Okay. Intriguing as Mr. Wei’s lifestyle is, let me ask my other question. Why us? This seems like a fairly straightforward job, delivering a legacy to a kid. You don’t need an investigator to do this. What is it, by the way?”

“Jade. Some valuable piece, something Mr. Wei got in China on one of his buying trips and used to wear around his neck.”

“Oh-ho, so he made buying trips to China? How do we know he hasn’t got another three dozen wives over there?”

“Why do I get the feeling you’re not taking this seriously?”

He gave me a look over his coffee that almost made me laugh. But someone around here needed to act like a grown-up, and neither Bill nor, I had to admit, old Mr. Wei seemed willing to play that role.

“Anyway,” I said professionally, “he didn’t got here that often. It was usually the brother who did the China trips. And to answer your question–assuming you still care about the answer–”

“Oh, I do, deeply.”

“–Grandfather Gao says he’s hiring us because he wants someone he can depend on, partly because of the other piece.”

“The other piece of jade?”

“The other piece of the job. Delivering the bequest and the letter is only half of it. We also have to deliver Mr. Wei.”

“You’re kidding.”

“He wants–wanted–to be buried in Hong Kong. Next to his second wife. In a mausoleum in Sha Tin on a windy mountain with a view of the hills and the water–” I broke off and looked at Bill, who was grinning yet again. “What?”

“You mean we’re taking the old two-timer with us? Carrying his cheatin’ heart home? Laying dem double-crossing bones to rest?”

“Ashes. And show some respect.”

“You misread me. I have nothing but respect for your Mr. Wei. What a guy. Maybe just by being in the presence of his mortal remains, I can learn something.”

“You,” I said with all the dignity I could collect, “will never learn anything. Anyway, the ceremony should be interesting. The half-brother will be there.”

“What, from New York?”

“Dr. Franklin Wei. He’s an orthopedist, in case you get your foot stuck in your mouth. Grandfather Gao says he’s planning to go to the funeral.”

“This is getting better and better. Why doesn’t he take the jade? And the letter? And the ashes?”

“According to Grandfather Gao he’s a little irresponsible. Married and divorced three times. Sequentially, not simultaneously.”

“I was about to ask.”

“I know you were. A wild and crazy guy.”

“Me?”

“Dr. Franklin Wei. New girlfriend every six weeks. Known at all the best clubs and hot spots. Cancels office hours to go to the ball game. May or may not actually show up in Hong Kong. Grandfather Gao didn’t ~want to risk it. Besides, it seems a little weird for him to be the one responsible for taking his father’s jade to the son of his father’s other son, under these circumstances.”

“I think this whole thing is a going to be a little weird.”

“Are you telling me you’re coming?”

He pulled on the cigarette again. “You remember, of course, that the last time we left town together you got hurt?”

“So did you.”

“Not as badly as you.”

“Whose fault was that?”

“Mine, no doubt.”

“If that’s an apology,” I said, “I accept.”

“I just wanted you to know what you’re getting into.”

“I’ll sign a waiver. So you’ll come?”

“Well, I’d still like to know why he wants me to. Besides the water buffalo thing.”

I gave him a look a little more serious than the ones I’d been giving him. “You’re thinking he’s expecting some kind of trouble?”

“The thought had crossed my mind.”

“Mine, too,” I said. “I tried to ask him. I said whatever small skills you and I might have, we were honored to put them at his disposal. I said we would exercise all our powers to accomplish the task he was setting us, and I was sure we could be most successful on his behalf if he were to tell us about any special concerns he had so we could prepare ourselves to meet them.”

“Elegant, setting aside the small. And?”

I shook my head. “He said, `Ling Wan-Ju, storm clouds often pass without rain, just as a dam can fail and flood a village on a clear, fine day.”‘

“Well, that clears that up.”

“You know Grandfather Gao never actually says everything he means. He thinks it works better if people find things out for themselves. And when he does talk,” I admitted, “half the time it’s in nature metaphors like that that I never understand.”

“And that’s why you’re so crazy about him?”

“I’m crazy about him, as you so delicately put it, because he’s wise, and kind, and fair. And he’s a wonderful herbalist, and he makes ~great tea, and he never treated me like a dumb kid, even when I was one. And you,” I told him, “should consider this: He’s the only Chinese person of my acquaintance, with the possible exceptions of my brother Andrew and my best and oldest friend Mary, who would consider giving you the time of day.”

“Well, you said he was wise.” He squashed his cigarette out. “You don’t think he could be setting us up?”

I was appalled. “Absolutely not! Grandfather Gao would never do anything to hurt me! If he’s expecting trouble, and he wants to hire us, it’s because he thinks we can handle whatever it’s going to be. Which is another reason I have to take this job. I can’t let him down if he’s thinking like that.”

Bill met my eyes and held them without speaking for almost longer than I could stand it. Then he looked back down and did some more cigarette-squashing. “When does he want us to leave?”

“Thursday! Thursday Thursday Thursday! Well?”

“What does your mother have to say? Not about the job, but about me going?”

“My mother?” I was surprised at the question, but I answered it with the truth. “You can’t expect her to feel anything but pure horror at the idea of me flying to the other side of the world with you.”

“I suppose not.”

“On the other hand, like I told you, she secretly thinks working for Grandfather Gao will keep me out of trouble for a while, and she’s always wanted me to go to Hong Kong. She says if I saw Hong Kong maybe I would understand better.”

“Understand what?”

“She never says. But I’m sure it has something to do with my shortcomings as a Chinese daughter.”

“So she approves?”

“She would walk off a cliff if Grandfather Gao suggested it, especially if it was for the good of her children. But she still doesn’t like the idea of me going alone with you. She had a solution.”

“Which was?”

“For her to come.”

I enjoyed the expression on his face when I said that almost as much as I like his grin.

“Oh, my God. What did you say?”

“What could I say? She’s my mother. But luckily Grandfather Gao said no.”

“You said yes?”

“She’s my mother.”

He stared. “And I thought I knew you. My God, a guy’s friends can turn on him.”

“Besides, I wasn’t sure you were coming.”

“I’m not sure I should. You might be lying. We’ll get to the airport, and there’ll be your mother, with her shopping bags and that flowered umbrella to hit me over the head with–”

“I’m going to hit you over the head myself unless you tell me whether you’re coming.”

I stopped pacing and stood in front of him, resisting the urge to stamp my foot.

“Well,” he said at last, “it’s certainly tempting. The other side of the world on someone’s else’s nickel? A chance to spend a week in a hotel with you?”

“Separate rooms.”

“A city where everyone smokes, where the weather’s tropical, where I can relive some of the high points of my misspent youth?”

“On separate floors.”

“Where the girls in the tight cheongsams sip mai-tais in booths in dim smoky bars until the Mama-sans call them over for you?”

“Separate hotels.”

“Where the Tsingtao flows like water and every other basement’s an opium den?”

“Separate land masses. Me on the Hong Kong side, you in Cowl.”

“Well, when you put it that way,” he said, “how could I possibly turn it down?”