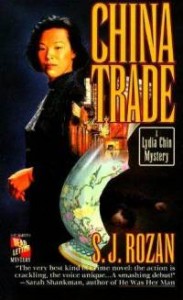

China Trade

Chapter One

I jumped a pothole in Canal Street as I dashed between honking cars and double-parked ones. A cab driver trying to beat the light screeched on his brakes and cursed me, lucidly in a language I don’t speak. Pinballing along the sidewalk from fish seller to fruit merchant to sidewalk mah-jongg game, I charged up Canal and down Mulberry. I pushed my way through the throngs of shoppers, who’re mostly local this time of year because Christmas is over but we’re coming up on Chinese New Year. I hopped curbs, squirmed sideways, and tried not to elbow old ladies as I raced to the old school building on Mulberry opposite the park. When I finally got there I stopped. I drew in sharp, cold air until my heart slowed and my breathing was back to normal. Then I calmly climbed the stairs and rang the bell.

I hate to be late.

I especially would have hated to be late to a business meeting with one of my own brothers. Though given the way this all turned out, it’s obvious to me I should never work for my family again.

In Chinatown, though, it’s not that easy. They can’t not ask you, and you can’t say no.

Not that it was Tim who’d asked me. He hadn’t been the one who called, and he hadn’t been mentioned. That told me a lot: It told me he didn’t approve of hiring me, though he hadn’t stopped it. Well, he couldn’t, could he? “Don’t get my little sister, she’ll screw up and I’ll never live it down.” No, he would have to pretend he thought I was the greatest private investigator since Magnum P.I. in order to save his own face; but I knew what he was thinking.

My family all thinks it.

The heavy wooden door, left over from when the building actually was a school, swung open. Well, maybe “swung” is too ambitious a word; it was more like it moved grudgingly aside. Nora Yin, one foot holding the grumpy door, stepped forward, took my arm, and steered me in.

“Hi, Lydia. Thanks for coming so fast.” She gave me a real, if worried, smile. Nora was tall for a Chinese woman, and broad-shouldered. She’d been a year ahead of me in high school. Nora had never passed notes in math class and had been a volleyball star besides.

“Well, you said it was important, and I wasn’t in the middle of anything.”

And hadn’t been for two weeks, I didn’t add. Business was slow.

“We’re in my office.” Behind her, the door clicked sullenly shut. “Come on.”

The building was the headquarters of Chinatown Pride, a group of community organizers, social-service deliverers, and general troublemakers. I liked them a lot. Their offices were on the third floor. The old gym and auditorium, which they used for public programs, were on the first floor, and their small museum was sandwiched between. They had bought the building from the city for a dollar. Now, looking at the peeling paint, listening to the stairs squeak, I wasn’t sure who’d gotten the better deal.

“How’s Matt?” I asked Nora as we climbed. I hadn’t seen Nora’s younger brother Matt for years now, but he’d been my first boyfriend. We’d had the sort of sweet, exhilarating romance that young teenagers carry on mostly in public, partly because you have no place to go, and partly because you’re not sure, not really sure yet, that you want to go there.

“Okay, I suppose. He’s still in California. I don’t hear from him much.”

Her voice had a chill in it that I was sorry to hear. They’d never been close; Matt was intense, impatient, a street-hockey player who’d scorned school. He’d sneered at Nora curled up in the Yins’ cramped living room doing and redoing her homework, and at her weekend volunteer projects. Nora had despised Matt’s cigarette-smoking friends and the hours wasted on street comers. After, to no one’s surprise, Matt had gotten involved on the fringes of a now-defunct gang, he’d been shipped off to live with relatives in northern California.

They didn’t think much of each other, I mused as we rounded the final landing, but family was family. I fight with my brothers all the time, especially Tim and Ted, but I’m not sure I’d like it any better if they just sort of pretended I didn’t exist.

“Well,” I said, “if you talk to him, tell him I said hi.”

Nora shrugged at that, then put on her professional face to enter her office at the top of the stairs.

There were three people waiting for us there. The one nearest the door–a white, middle-aged man, stoop-shouldered, with thick gray hair–stood promptly as Nora and I came in, his eyes on Nora’s worn vinyl floor like a little boy not entirely sure of what well-mannered behavior was but earnestly trying to remember. He held an earthenware teacup, the kind without a handle, and the air was fragrant with jasmine-tea.

Nora stopped inside the doorway to do the introductions.

“Lydia, this is Dr. Mead Browning. Dr. Browning was on my thesis committee, from the Art History Department.”

Nora’s Ph.D. thesis subject was Images of Woman in Tang Dynasty Art, and her committee, I’d heard, was a triumph of her diplomatic skill.

Dr. Browning smiled bashfully when he shook my hand. He didn’t meet my eyes, but probably that was my fault. My mother always says I stare.

Next to Dr. Browning a slim, sixtyish Asian woman remained seated as she extended her hand to me. She wore a soft, perfectly fitted black wool dress, small gold earrings with what looked like real pearls in them, and a single strand of, what also looked like real pearls, around her neck. I don’t know anything about pearls: maybe they only looked real because of the air of grace and authority of the woman who wore them.

“And this is Mrs. Mei-li Blair,” said Nora. “Mrs. Blair, this is Lydia Chin.” Nora moved around her desk to sit in the old swivel chair behind it. The chair squeaked like the stairs. I shook Mrs. Blair’s hand, thinking her name was probably supposed to mean something to me. Her hair had turned almost completely to silver and was cut into a satiny cap of exquisite precision. My hair, when it turns, will probably go messily gray, and my haircuts won’t hold their organization any better when I’m sixty than they have since I was twelve.

The other person in the room was a man, Chinese, two years and two days older than me. He perched on the windowsill and fumed. That was Tim. I offered to shake hands with him, too, but that just seemed to annoy him. Nora hid a smile.

I stuffed my yellow hat into my jacket sleeve and hung the jacket on the back of my chair while Nora poured me tea. Then she got right down to business.

“We’ve had a robbery,” she said. “We’re hoping you can help.”

“A robbery? When? Was anybody hurt? Why didn’t you tell. me?” Before I could stop myself my eyes flew to Tim, searching for bruises, cuts, signs of an armed struggle.

“We are telling you, Lydia.” Tim’s voice was exasperated. “And it wasn’t a robbery, it was a burglary. No one was here and no one saw them. No one was hurt,” he added, sort of extraneously. “People don’t usually get hurt during the commission of a burglary.”

“Sometimes they do,” I said, before I could tell myself to shut up. “Violent criminal activity often happens in the course of the commission of non-violent crimes.” I was suddenly appalled to realize I sounded as pompous as he did.

“I’m a lawyer, Lydia,” Tim reminded me pointedly. “I know something about criminal behavior.”

I squelched the obvious crack. “Well, tell me about your burglary.” I looked back to Nora and smiled.

Nora picked up her cue. She shrugged at the semantic difference between “robbery” and “burglary.” “Someone broke into the basement and stole some things,” she said.

“What things?” I asked. “What do you guys keep in the basement?” So far as I knew, Chinatown Pride wasn’t exactly rich in assets. I couldn’t imagine anything from its basement being worth hiring a private investigator to find.

Nora looked at Tim, who looked out the window, frowning. “I have to tell you,” Nora said, “that Tim doesn’t approve of the way we’re going about this.”

“You don’t actually have to tell me,” I said. “I guessed.”

“As CP’s legal counsel he believes we should have called the police,” Nora went on, before Tim could say anything. “The Board did meet and discuss doing that, but for what seem to us like good reasons we don’t want to. We want to see what you can do first.”

“Well, I’ll be glad to help however I can,” I said cooperatively, professionally, and maybe just a touch smarmily, for Tim’s benefit. “What was stolen? And why aren’t you telling the police?”

Nora’s eyes, this time, went to Dr. Browning. He looked quickly down at his teacup. Nora turned back to me. “A month ago the museum got an unexpected gift. The Blair porcelains–do you know about them?”

I shook my head. Tim barely hid a frustrated sigh. Now that wasn’t fair, I thought. I can’t be expected to know about everything there is. If he weren’t CP’s legal counsel I’ll bet he wouldn’t know about the Blair porcelains either.

“What are the Blair porcelains?” I asked Nora as though it were a natural question.

Nora turned to Mrs. Blair, who took up her silent offer to be the one to answer me.

“My husband, Hamilton,” Mrs. Blair said, in a voice that was quiet but not weak, “was a collector of Chinese export porcelains. Upon his death three months ago, I was faced with a decision about the future of his collection.” She stopped to sip her tea. She had a slight Chinese accent in her British-inflected speech: English was not her native language, but she had been speaking it, quite correctly, for a long time. “My husband, Miss Chin, was something of a recluse. He collected strictly for his own pleasure and mine, insofar as I could appreciate the beauty of the objects he loved so. The main pleasure I took from the collection was watching Hamilton’s excitement and joy as each new piece came to us.”

She stopped again, and though she drank, I didn’t think thirst was what had put the catch in her voice.

She lowered her cup and continued. “I didn’t share Hamilton’s passion for these porcelains, but he was devoted to them. After he died, it did not seem right to me that an aging woman in an empty house should be all the companionship the pieces he had loved so much would have.”

I finished my tea and half-turned to put my cup down on the coffee table. As I did I noticed Dr. Browning smiling slightly, looking at his knees. There was a little color in his cheeks, too.

Mrs. Blair went on: “There were many options for the disposition of the collection, and I had no basis for a decision. I consulted Dr. Browning, whom I had not met but whom Hamilton had greatly respected. After discussions, with him and with Nora, I had given the entire collection to the museum here, as a gift”

I was astounded. “To CP?” I bit my tongue to keep from asking, Something that valuable?

Mrs. Blair smiled. “My family is from Hong Kong, not Chinatown, but I am Chinese. My brother owns an import-export firm further up Mulberry Street, but until Dr. Browning told me about Chinatown Pride, I had no idea there was a museum of any sort in this neighborhood. I feel, and Nora confirms this, that my ignorance is not unusual. If my gift can help raise this museum’s profile in Chinatown and in the city at large, I would consider it an honor.”

Nora turned to me. “When we started the museum,” she said, “‘we wanted people–kids, especially–to come here to learn about what an ancient civilization they come from. To start being proud of being Chinese, instead of ashamed of being different.”

“And it works,” I said, recalling giggling groups of third graders poking each other in awe at the Peking Opera costume exhibit the day I’d taken my oldest nephews there. “It’s beginning to catch on.”

Nora nodded. She gestured the teapot around, but Mrs. Blair and Dr. Browning didn’t want any more and Tim only drinks Lipton’s. “The museum’s grown slowly,” she said. “The Blair porcelains are the most important gift we’ve ever gotten. There were other museums that were hoping for this collection and consider themselves better equipped to display and protect it. The Blair collection has quite a reputation among porcelain experts, even though almost no one has actually seen it.”

“They haven’t seen it?”

“As I said,” Mrs. Blair spoke in a voice that was used to not having to be raised to be heard, and that was also, it seemed to me, used to being understood the first time, “my husband was a recluse. He found most people tiresome; greedy, and hypocritical. Without honor, and full of secrets. His collection was his refuge. Porcelain, he often said, had no secrets: It is surface beauty applied over a perfect foundation. My husband did not invite other people to share his refuge.”

Nora looked at me with a steady gaze. “Lydia, I don’t know how much you know about the museum world, but if it gets around that we couldn’t hold on to this gift it would mean a tremendous loss of face for us. We might never get another donor to consider us again.”

I began to get the importance of this to Nora and CP. “That’s what was stolen? The Blair porcelains?”

“Not the whole collection,” Nora said. “Two crates.”

“How much is that?”

“Nine pieces,” Dr. Browning unexpectedly answered. His voice was thin and reedy, and almost apologetic. “A tenth of the whole.”

“It’s about as much as two people, or possibly one person, could carry away,” Nora added.

“Crates?”

“About this big.” Nora made a box the size of a small trunk with her hands.

“Where were they stolen from?”

“Our basement. We had an alarm system put in and iron grilles on the windows. The grilles were cut and the alarm system had been disabled. It never went off.”

“Disabled? How?”

“A device that kept the signal transmitting even though the wire was cut. Apparently it’s not hard to do.”

“No, it’s not,” I said, absently. I knew that was true, though I didn’t, myself, know how to do it. “But it takes planning ahead . Who knew the porcelains were here? ”

Nora glanced at Mrs. Blair. “As far as we know,” Nora said, “only Tim, myself, Dr. Browning, and Mrs. Blair.”

“What about the rest of the Board?”

“Since the theft, everyone knows. But they didn’t know when they were coming or when they got here. Those were the kind of details I dealt with, as museum director. No one asked. But,” she added, “whoever took them doesn’t have to be someone who knew what they were stealing.”

“You mean, they might have been just regular old thieves, and they happened on the Blair porcelains?”

“Well, it seems to me if they had come because of them they’d have taken them all. Dr. Browning says the things in those boxes aren’t even particularly special.”

Dr. Browning shook his head. “Not any more than the rest of the collection. It’s all very, very special, of course.” He looked up suddenly, his gray eyes wide, as if he were afraid he’d be misunderstood.

“How did you discover the theft?” I asked Nora.

Dr. Browning, again unexpectedly, answered that one, too. “I discovered it.” He blushed, as if that had been an improper thing to do, discovering a theft. “When I came in yesterday afternoon to continue my work.”

“Your work?”

That had been enough for Dr. Browning. His eyes were back to examining the floor.

“Dr. Browning is inventorying and cataloging the collection for us,” Nora told me.

Puzzled, I asked Mrs. Blair, “Don’t people who have collections like this have inventories?”

“My husband had a list,” Mrs. Blair answered, “but I’m not entirely sure it’s complete. The new pieces he’d recently acquired had not, I believe, been added to it.”

Dr. Browning shook his head, as though he didn’t believe they had, either.

“I’m surprised,” I said. “I mean, even just for insurance, you’d think someone would want to be up-to-date on his inventory.”

Mrs. Blair’s smile was indulgent and tinged with sadness. When he was alive, I was willing to bet, his casual attitude toward things like that probably drove her crazy. Now she missed it.

“That’s what I thought about the inventory, too,” said Nora. “But apparently this isn’t unusual.” She looked to Dr. Browning.

“No, it’s not.” Dr. Browning answered a second late, as though he wasn’t sure he was the one being spoken to. He smiled the bashful smile again, but kept his eyes on his shoes.

“A true collector knows every piece in his collection. He doesn’t need a list, any more than you need a list of your friends.”

Something I had just said reminded me of a question I hadn’t asked. “Were these pieces insured.”

“The collection is,” Nora said, after a hesitation that was, I assumed, another invitation to Mrs. Blair. “But those particular crates were the new acquisitions. Because Mr. Blair hadn’t I gone through the process of adding them to the inventory list yet, those pieces weren’t covered.”

“Those were all the new acquisitions? They all happened to be, together?”

“They didn’t ‘happen’ to be together.” For the first time I heard the kind of frost in Mrs. Blair’s voice that I associate with upper-class Hong Kong women. “I had them packed that way, to make Dr. Browning’s task easier.”

“Strange,” I mused. “That that’s what was stolen and nothing else.”

“Perhaps strange,” Mrs. Blair answered. “And perhaps coincidental. Any two crates would have included only certain pieces, about which we could have said it was strange that they, and not others, were stolen.”

“I suppose,” I agreed, not sure I supposed any such thing. I turned my attention back to Nora. “Well, on principle I hate to agree with Tim, but the police have resources I don’t have. Why aren’t you going to them?”

Nora looked at Tim. His jaw was tight and his ears were crimson. Childhood memories of times when his ears were that color gave me a strong urge to hide under the desk

Nora poured more tea for herself and for me. She warmed her hands around her teacup. “Dr. Browning tells me it’s almost impossible to recover stolen art. And the police have other priorities. We decided that the damage it would do our reputation if we made this public would far outweigh whatever advantage the police would have over our doing this privately.”

I looked over at Mrs. Blair, wondering how she felt about the theft of Hamilton’s porcelains being handled without benefit of law enforcement.

As if reading my mind, Mrs. Blair smiled. “I concur completely in this decision, Miss Chin. Nora consulted me on behalf of the Board before the decision was final. The police, as Nora said, have their own priorities and restrictions. As there is no possibility of an insurance recovery, I see no advantage in calling them in.”

“Restrictions?” I looked from her to Nora.

“The police,” Nora said, replacing a stray freshly-sharpened pencil into her freshly-sharpened-pencil cup, “are limited in the methods they’re permitted to use. In the sense, I mean, that if a crime’s been committed, they have to be as interested in catching and prosecuting the criminals as in recovering the property. We’re not. We want the porcelains back first. We’d like to see the criminals caught if possible, but that’s secondary.”

“Do you mean,” I said, “that you’d be willing to deal with whoever has them?”

Nora glanced at Tim, who scowled.

“We might,” she told me.

“Can you afford to do that? Buy them back.”

“Not for their market value, absolutely not. But maybe we could… work something out.”

“That’s where I come in?”

“Well, we have to find them first. Someone on the Board suggested hiring a private detective, and of course you were the one we all thought of right away.”

Of course, I thought. Even poor Tim must have thought of me right away and frantically tried to find some way to keep his busybody, embarrassing little sister out of his business.

“And I again concurred,” Mrs. Blair assured me. “I understand that you’re young and relatively inexperienced but Nora gave you quite glowing notices. And being Chinese . . .”

She didn’t finish that, and I wasn’t sure what she hoped would come of my being Chinese.

I looked around the room. Dr. Browning was gazing at his shoelaces. Tim wouldn’t look at me. Mrs. Blair was smiling gently. I turned to Nora. She looked at me with something like pleading in her eyes. Coming from her, that was startling, and I found myself feeling touched and suddenly protective.

“All right,” I said, in my best client-relations voice. “Art’s not my specialty, but I have a colleague who’s experienced in art cases. I’ll need particulars, and I’ll do what I can.”

After all, I thought directly at Tim, who seemed to find glowering out the window as fascinating as Dr. Browning found staring at his shoes, if I needed a lawyer, I’d go to you. That’s what you do, this is what I do. I don’t have an advanced degree and you don’t have a gun.

And just because I’d never heard of the Blair porcelains didn’t mean I couldn’t find them.