Mandarin Plaid

Chapter One

It’s not that I don’t like spring in Madison Square Park–I’m a fan of the fat little buds on the trees and the sun sparkling off the puddles. It’s just that I’m not usually strolling through here with fifty thousand dollars, looking for the right trash can to drop it in.

My footsteps crunched gravel on the curving path. The air was chilly, but the soft March sun grazed the back of my neck. Snowdrops and bright crocuses were up everywhere.

The sweat tickling my spine had nothing to do with the weather.

Squirrels chased each other down trees and over spring-soggy grass. The dogs in the early-morning run chased each other, too, while their owners chatted by the fence. The fresh breeze smelled sweet.

My skin prickled.

I kept my eyes jumping, trees to paths to dogs and their owners.

On a bench up ahead, Bill Smith, my sometimes-partner, pretended to read a book. He had a thermos of coffee beside him, which was a good thing. His job was to watch my back, and then, when I was out of sight, to watch the trash can until someone came to withdraw my deposit. That could take a while.

The client hadn’t asked for that, but my brother had.

When I’d met Genna Jing and her boyfriend, John Ryan, at my brother Andrew’s loft the night before, all they wanted was someone to make the drop.

“I would do it,” John Ryan said. He sipped white wine as he and Genna sat hip-to-hip on Andrew’s angular 1950s sofa. “But Genna doesn’t want me to. And I certainly don’t want her to. Then someone reminded Genna she had a friend whose sister was a private eye.”

Ryan was blue-eyed, well-tanned, wearing a black T-shirt under a poplin suit the color of dark honey. His short wavy hair was the same color. Genna Jing, beside him, had the silky hair, porcelain complexion, delicate features, and tiny ears of the classically beautiful Chinese.

I don’t have those, though my mother has always said I’d be almost pretty if I’d let my hair grow and keep my mouth shut. And wear skirts more often.

Genna Jing was wearing a skirt, a tight knee-length one with a slit up the side, and a short-sleeved silk blouse with a Mandarin collar–a cliched Chinese vamp outfit, except both pieces were plaid. Different plaids. I wasn’t sure whether my mother would have approved, or not.

“Brad told me,” Genna said. “My secretary. He’s a friend of Andrew’s. Do you know him?”

“No.”

“Well, he was looking for a job when I was looking for a secretary, when I started on my own. Andrew put us together.” Genna Jing indicated my brother, doing something precise in the stainless-steel kitchen across the loft.

My brother Andrew is four years older than I am, good looking, with a smooth forehead, a sharp nose, and eyes that, if you ask me, twinkle like our father’s used to. We have three other brothers, and nobody else’s eyes seem to do that. Andrew’s a photographer. With equipment as exacting and precisely kept as he is–lenses ground and polished in Switzerland; carbon steel tripods that wouldn’t jiggle in an earthquake; lots of different 35 mm, 4″ x 5″ and 8″ x 10″ camera bodies each just right for a different kind of film–he produces images, sometimes things and sometimes people, of such sweet and chaotic darkness that they can take your breath away. My mother just thinks they’re confusing, but Andrew’s very much in demand.

“It’s just a drop?” I asked Genna Jing and John Ryan. “Leave the money where they said and walk away?”

“No way, Lyd,” Andrew called, clinking ice into two 1965 World’s Fair glasses. In demand or not, and even though he was the person who’d brought me this client, he was beginning to annoy me. “Listen, you guys,” he addressed the pair on the sofa. “When you said you wanted to meet my sister I thought you wanted something investigated. You know, researched, phone calls and stuff. What you’re asking her to do-”

“Is what I do,” I finished. Actually, I’d never done this before, but every P.I. I know has been asked to make a shady payoff at some time or other. It’s one of the services the profession offers.

“Lyd–”

I threw Andrew my steeliest look. He’s the brother I use that look on least often, so it sometimes works. He frowned, but he closed his mouth and went back to slicing limes. I turned to the pair on the sofa. “Then what? They pick up the money, and you get your sketches back?”

Genna glanced from John Ryan to me. “I don’t think they’ll give them back,” she said. “They’ll probably just throw them away.”

“Wait, I don’t get it. Someone broke into your studio and stole your sketches, right? For your line for next spring?”

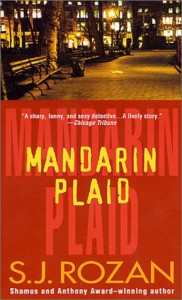

She nodded. “The first full spring line for my own label, Mandarin Plaid.”

“And you’re paying fifty thousand dollars but you’re not getting them back? What’s the money for?”

“Well, it’s not like the drawings are originals or anything.” Genna spoke with the unease of a polite person who doesn’t want to patronize her listener by explaining the obvious. To me, though, this wasn’t obvious.

“You mean you have copies?”

“These days, everything is done with copiers and fax machines.”

Genna gave me a small smile. “There are no originals anymore.”‘

“Then why pay the ransom at all?”

“Because if I don’t pay,” Genna said, squeezing John’s hand, “they’re going to ruin me. They’ll abort my career before it starts.”

“How?”

“They’re going to sell them. To Mango, or Bizniz, or someplace like that.”

?She said this seriously, her voice soft with that damper of shame that comes when someone is about to do something bad to you and you can’t stop them.

I knew those names: national chains of inexpensive, up-to-the-minute clothes. I shopped in them, because I liked the styles and the prices, but I didn’t shop there often, because my mother scorned anything I bought from them as “bad cloth, bad sewing.” Then she’d fix me with a meaningful stare and announce, “Only a fool thinks cheap saves money.”

Andrew, the lime slicing completed, came over and handed me my Swedish sparkling water, something I know he goes all the way to the Upper West Side to buy. He leaned back in a molded plywood chair of the same vintage as the sofa.

“They’d buy them?” I asked. “Stolen designs?”

Genna didn’t answer right away. John took it up.

“Sure as hell,” he nodded. “I don’t know how much you know about the fashion business, but it’s cutthroat. Right now, Mandarin Plaid’s ready to take off. We’ve been getting a lot of press lately. People are expecting big things from Genna. Her first show is next week, Market Week.”

Andrew broke in to say to me, “Market Week is when–”

“When the designers show next season’s clothes. In the big tents in the park behind the library,” I finished. Andrew’s my favorite brother, mostly because he assumes I’m a total idiot less often than the other three do; but he still does it sometimes.

Genna gave me a raised-eyebrow look of understanding. John just nodded. He must not have any brothers, I thought.

“I’m not doing the tents,” Genna said. “I’m not big enough. A friend is lending me his loft. But I’ve invited everyone, and there’s been some talk. It could be okay.”

“Bigger than okay,” John said. “It’s going to be huge. Enormous. Gigantic. But if Genna hits with this line for fall, and then a chain like Mango or Bizniz starts putting out Genna Jings for spring before we do, it’ll be a disaster.”

The magnitude of this was beginning to shape up for me. I asked another question. “Now that the sketches are stolen, why don’t you think they’ll sell them to Bizniz or somebody anyway, after you pay the ransom?”

“We thought about that,” John said. “But it’s risky. They might run into an honest person at Bizniz. Surprise! Then what?”

“And you don’t think they’ll take that risk?”

John shook his head. “I don’t think they’re pros. In fact, to do a thing like this I think they have to be a little crazy. There have to be easier ways to make a buck, don’t there? Even illegally.”

I wasn’t sure. So far, this seemed pretty easy to me.

“They might try to sell them out of spite if Genna doesn’t pay, John went on, “but I don’t think they’ll risk it if she does. Anyway, in terms of risks, that’s one I think we have to take.”

“Do you have any idea who they might be?”

Genna shook her head. Her hair brushed her shoulders and settled perfectly back into place, but it seemed to me that something in her eyes didn’t.

“It had to be someone who knows I’m about to have my first show, but that’s no secret,” she said. She sipped at her wine. “And someone who would know what to take. But that could be anybody.”

“Not really anybody,” I said. “How did they know where to find what they wanted? That they weren’t grabbing up rejects? You said your alarm went off but they were gone by the time the cops got there. That’s quick work. It means they knew just what they were doing.”

“By the time I got there,” John put in. “I beat the cops by five minutes.”

“But what’s the difference?” Genna’s voice, steady and controlled until now, began to quaver. “Even if we knew who it was, I’d have to pay, wouldn’t I? Unless we could find them and get the sketches back right away. And be sure they hadn’t copied them.” She bit her lip and looked away.

John wrapped his arm around her shoulders. “It’s okay, Gen,” he said softly. To me he said, “She’s right. They want the money tomorrow morning. The most important thing is to stop them. Then to get Genna’s show done. Then to find out who these bastards are.”

“I’m sorry,” Genna said to me, with a weak smile. “I’m not usually like this. But I’m just exhausted. I’ve been pushing so hard to get the show done. Things keep going wrong, people backing out at the last minute–it’s been a nightmare. But this is the worst.”

John kissed Genna’s pale-silk forehead. He turned to me. “Can we just do this?” he asked. “Can you just make this drop, and we’ll worry about everything else later?”

“Yes,” I said, over Andrew’s “No.” His was louder, but mine was, firmer. Narrowing my eyes at my brother, I went on, to Genna, “But if someone did this to you now, why won’t they do it next season, even if you pay them? And over and over?”

“They won’t be able to.” Genna swallowed and brought her voice back under control. “It’s the timing. If my show’s successful–”

“Which it will be,” John said.

She smiled gratefully at him. “Which we hope it will be, then I’ll be established. After a few seasons it doesn’t matter if Bizniz or Mango or anyone is selling things that look like Genna Jings. It’s only in the beginning, if the spring line of Mandarin Plaid looks like something they already have at Bizniz, then I’m in trouble. Then my investors would pull out, and I’d never have a line.”

That reminded me of another question. “The ransom money,” I said. “Where’s it coming from? From your investors?”

“Oh, God, no. It would be a disaster if they even found out about this. They might lose confidence, no matter what we did. They’d pull out.”

John said, “Genna’s getting the ransom from me.”

At that, Genna’s face changed. She looked down at Andrew’s polished wood floor. “No, I’m not.”

“Genna…”

“I got it already.” Her words were so hurried I almost missed them.

Ryan didn’t miss them, but it took him a minute to know what to do with them. “You what?”

“John, I told you I wouldn’t take your money, and I don’t want to talk about it now.” Genna turned to me. “I borrowed the money. It’s right here.”

She drew a thick envelope from her metallic handbag. “It’s in fifty-dollar bills. That’s what they wanted.” She handed the envelope to me. It was heavier than I would have thought.

“No,” Andrew said as I took it. “Lydia’s not doing this.”

“Andrew,” I said sweetly, “buzz off.”

“Lyd, this could be dangerous.”

“It won’t be. And you sound like Ted.” I figured that would stop him. Ted’s the oldest of us and pretty stuffy. Andrew doesn’t like to sound like Ted.

Andrew opened his mouth again. “And like Tim,” I added, just to be safe. Tim’s the youngest of them, the brother between me and Andrew. He’s a lawyer. Nobody likes to sound like Tim.

“Give me the details of the drop,” I said to Genna, putting the envelope in my briefcase.

“Genna,” John broke in. I could hear the effort it cost him to keep his tone reasonable. “Where did that money come from?”

“We’ll talk about it later.”

“You borrowed it? What the hell did you do, max out your credit? Genna, baby, are you nuts? You’re going to need that as soon as things get rolling.”

“John–”

“Baby, what’s wrong with you?” John pleaded. “I’ve given you money before. What’s your problem now?”

“That’s an investment.” She didn’t raise her voice; if anything, she spoke more quietly. “Every penny of that money is accounted for. If Mandarin Plaid hits, you’ll get it all back. And more. If not, it’ll be a great deduction. But I don’t think you can deduct ransom payoffs.”

“I’m not sure,” I said. Andrew gave me a you-really-are-crazy look. “No, what about kidnap ransoms?” I defended myself. “That’s the cost of doing business. So’s this.”

I might have been right and I might have been wrong, but it was clear I wasn’t speaking to the issue.

“John, I don’t want your money. That’s not who I am.” Genna gave John a look so steely I found myself hoping the one I’d given Andrew was as good. I liked her for it. Not all Chinese women have a look like that. My mother considers it unseemly.

“We’ve had this argument before and I don’t think Andrew and Lydia need to listen to it.”

John didn’t speak, but his eyes held Genna’s as though he was willing her to do what he wanted. Her face was calm, and she didn’t look away. The contest was silent and brief John Ryan suddenly gave up, and stood.

Wineglass in hand, he strode through the room to the open front windows, moving as though he had to force his way. He glared into the street, one hand on a window frame. Genna turned to me with the look women give other women when their men are misbehaving.

When she spoke, all she said was, “Can you do it?”

“Of course,” I said.

“Lyd–”

“I took the job, Andrew.”

“I know. I know.” He sounded resigned. “But at least don’t do it alone, okay? Take Bill with you?”

“Ma would kill you if she heard you say that.”

“Ma will kill me and chase me through all the caves of hell with a cleaver if you get in trouble and it’s my fault.”

“That’s true.” I grinned.

“Who’s Bill?” Genna asked.

“Another investigator, someone I work with a lot. Sort of my partner.”

“Your mother doesn’t like him?”

“She hates him.”

“Let me guess: he’s not Chinese.”

Genna and I smiled, the same smile.

Then Genna’s faded. “I don’t know,” she said. “They said to keep this quiet. I don’t know if it’s a good idea to bring in so many people. Will you feel safer if he’s there?”

“Not safer.” Dispel that thought right away, that Lydia Chin might need someone to keep her safe. “Dropping money that someone’s waiting for isn’t likely to be dangerous. The bad guys will be as interested as we are in having things go smoothly. But if Bill were there, he might get a chance to see who makes the pickup.”

“They said no cops,” John growled, from the window.

“We’re not talking about cops. Not to grab the guy, just to have a look at him. Even if Bill doesn’t follow him–” which I knew he would, especially if I told him to, and probably even if I didn’t “–he can describe the guy to us. Maybe it’ll turn out to be somebody you know.”

“What if it is?” John asked testily, looking out over the purple spring evening on Twentieth Street. “What are we going to do about it?”

“That will be up to you. But at least you’ll know.”

Which is how I came to be in Madison Square Park on a bright March morning, heading for the fifth trash can in from the corner, which Bill had already scoped out so he’d know where to plant himself.

Madison Square Park, which spreads north and east from Twenty-third and Fifth, is a happening place in the early morning. Rising young executives hurrying to work maneuver around dogwalkers and their dogs, while others, whose positions in their companies are either more secure or more hopeless, sit drinking coffee and chatting before they go on. Some of the benches are occupied by the homeless, who stretched out on them the night before and are in no hurry to move anywhere. At this time of year, this early in the morning, half the park is in shadow from the tall buildings on Madison, while the sun billows through the budding trees and into the other half. The line between the two halves keeps moving. If you watch you can see it.

My instructions, which Genna had gotten over the phone, were to leave the envelope in the can and keep walking. I’d been given a time, 7:30, and a warning: no funny business. The thief had been told I was a friend of Genna’s who was doing this for her because Genna was spooked. I didn’t know if he believed that, but I didn’t care. I was too annoyed that, although this was my case, Bill was going to have all the fun.

Once I dropped off the money I’d have to follow the instructions to make myself scarce; to the client, a successful operation meant having the exclusive rights to her own sketches again, and my first responsibility was not to jeopardize that. I’d probably head back to Chinatown and my office, where I’d call Genna, report in, and sit and wait for Bill to call me.

Bill, meanwhile, would be waiting for, spotting, and then shadowing the bag man all over town.

I looked at him, up there ahead on his bench, probably full of adrenaline already, edgy to start the cat-and-mouse. He hides rush better than I do–he’s been in this business longer, and he’s more self-control in general–but I know he feels it.

I was feeling a little of it myself as I neared the trash can, even though I completely expected nothing at all to happen. Reaching into my pocket to pull out the envelope, dropping it casually on yesterday’s Post and a half-eaten hot dog, I felt that jumpy sense of triumph you get when an important job’s successfully done. Plus that irrational disappointment that now there’s no more to do, that now it’s over.

That’s the part I was wrong about. It wasn’t over.

I heard the bang and whine as soon as I’d turned away from the can. Instinct took over from thought. Something caught me in the face as I dove behind a tree. I rubbed at it: a splash of mud thrown up by the impact of the bullet. The second shot sprayed gravel from the path into the air. Dogs barked and howled. Executives hit the dirt. Screeching birds wheeled into the sky. People ran and yelled and ran some more.

I crouched in the mud and forced myself to count to sixty. I gave it up at five. My heart was pounding and time took forever.

I peered out. Around me were people lying still like fallen park statues. Even the squirrels were hiding; nothing moved. Somewhere at the other end of the park a dog was barking, over and over. At that end people were running and shouting. I looked for Bill. His book was lying alone and open on the bench, its pages flipping forlornly in the wind. No third shot came. I emerged from behind my tree.

In the distance, approaching fast, I heard the wail of a police siren. People stirred and stood. I moved a little way from my tree and blended into the quickly gathering crowd. I examined the faces around me. Fear, anger, and confusion bathed them all. I glanced into the trash can.

The envelope, of course, was gone.